-

A Development Strategy Is Necessary to Unlock Nigeria’s Vast Gas Potential – Engr. Chichi Emenike

- by chukwuma89@gmail.com“Gas is Revenue. Gas is jobs. Gas can guarantee us economic security.”

These were some of the affirmations shared by Engineer Chichi Emenike, the Head of Gas Ventures, Neconde Energy, at the virtual roundtable session by Nestoil on Thursday, 20th August 2020.

The roundtable session themed “Gas: The New Frontier for Nigeria’s Sustainable Growth,” centred on gas as a sustainable means of energy and how to sustainably develop the industry at scale.

The engineer pointed out that Nigeria is more of a gas-producing nation than crude oil.

“We have unproven reserves of up to 600TCFs (Trillion cubic feet) of gas yet unlocked. We haven’t touched a tenth of our gas reserves,” she said, explaining that crude oil drilling activities generate most of the gas used in the country.

“The world has moved on from crude oil, and we need to recognize that in Nigeria.”

She also spoke about the need to invest in the gas sector as other countries have moved on to more sustainable and stable forms of energy. The Neconde Engineer highlighted the instability of crude oil prices worldwide due to geopolitical situations, and the need to establish stability with gas, by opening up the domestic gas economy.

“We have seen what has happened this period over the past five months; Crude oil prices went south, but gas prices remained fairly stable.”

Engineer Chichi Emenike also touched on the significant issue in the gas industry, which is funding. “Funding in the gas market,” she said, “is contingent on a bankable market. You want paying customers”. She cited this as the problem with investors as they do not have a clear line of sight regarding investments. This is due to the lack of a Petroleum Industry Bill, Forex mismatch and liquidity issues with the power sector, which is the largest offtake of gas.

0chukwuma89@gmail.com

-

Building Power Plants in a Regulated Price Regime

- by chukwuma89@gmail.comIt is common sense that you cannot sell a product that you don’t have and cannot get from any available seller. Similarly, as Nigeria’s 11 Distribution companies (DisCos) increase metering of the population and repair their aged infrastructure, as the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN) improves beyond its current wheeling capacity of 5,400MW, and as gas supply increases, generation capacity will quickly become a bottleneck in spite of promises of 25GW by 2025. We have heard promises of an improved Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry (NESI) before, but for one reason or another, they never come to pass.

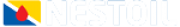

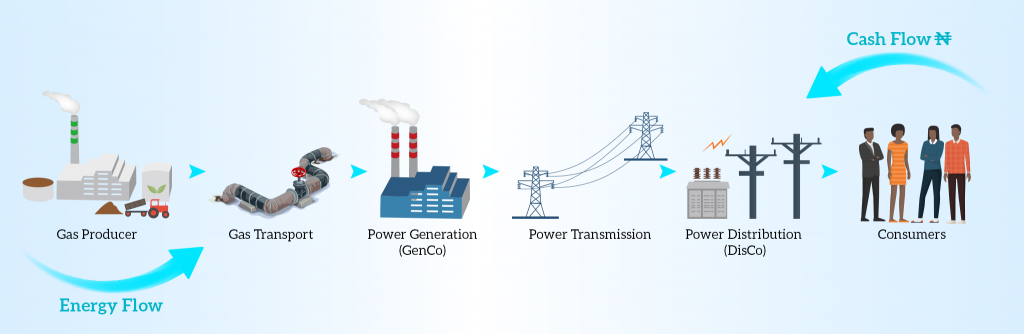

Figure 1 is a pictorial depiction of Nigeria’s electricity value chain, which starts with gas production and culminates in the consumer. It shows energy starting from gas production on the left-hand side of the picture to the consumers on the right-hand side, while revenue is collected from consumers and used to pay each segment of the value chain to the left.

Figure 1: Nigeria’s electricity sector value chain

Figure 1: Nigeria’s electricity sector value chain Generation companies (GenCos) are literally the “engine room” of the power value chain and strategically reside in the middle of the chain depicted in figure 1. For this engine room to work optimally, gas producer and transport to the left must reliably supply gas fuel as needed without disruption, while transmission and distribution to the right must evacuate generated power to create room for more power to flow.

Clearly, without GenCos working optimally and with the capacity to reliably produce power in excess of what is actually needed by the DisCos, the country will run into deficiency as the gas side, transmission and distribution side get fixed.

Nigeria’s current installed capacity of 12,552MW generating capacity is well below the standard of a developing nation, and this primarily, amongst other factors outside the ambit of this article ensures that it remains a consumer nation instead of a producer nation, which it should be aspiring to.

For over a decade, installed capacity has remained relatively flat with a sustained actual generation of less than 4,000MW, which is a meagre 31 per cent of the installed capacity. In a July 2016 report titled “Powering Nigeria for the Future”, PWC stated that Nigeria’s annual per capita power consumption in 2015 was 151kWh. Average power utilisation of 8 developing countries including Sri Lanka at the lower end (588kWh), Vietnam (1,465kWh) and Egypt (1,877kWh) in the middle of the pack, and Ukraine at the top (3,234kWh) showed that Nigeria should have a power consumption of at least 1,213kWh.

Factoring population growth at the time of the report, it was expected that the average per capita power consumption of the 8 countries would grow to 1,818kWh by the year 2025, with Nigeria’s expected to increase to 433kWh. The expected growth in Nigeria’s number is so far not happening, even though its population has grown from 182 million in 2015 to over 200 million in 2020, further reducing the per capita power available to the population since the actual power available has not grown since 2015. Over a 15-year period from 1995 to 2010, Vietnam grew its per capita power consumption from 159 to 1,035kWh, representing an increase of 6.5times.

Between 2005 and 2015, Vietnam with a population of 93.4million, increased their generation capacity from 12GW to 40GW, i.e. a 236 per cent increase. Vietnam’s GDP per capita increased from $687.48 in 2005 to $2,085.10 in 2015 mainly due to industrialisation, while Nigeria’s grew from $1268.38 to $2730.43 in the same period mainly from oil and gas. A significant increase in Nigeria’s per capita power consumption of at least 6.5 times is, therefore, both feasible and viable in the country if a different approach is applied in dealing with the power sector.

It is clear that Nigeria must, as a matter of urgency, grow its power generation capacity to at least 40GW by 2031. The current Siemens deal signed by the Federal Government promises to increase capacity to 25GW by 2026 by resolving some transmission, fuel and distribution issues, rehabilitating some existing ailing plants and adding about 7.6GW. This new 7.6GW would include the 4,000MW slated to be built by NNPC. It would, therefore, appear that yet again, we are doing the same things and expecting a different result.

Currently, the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading PLC (NBET) pays the existing grid-connected GenCos from 38 per cent to as low as 11 per cent for the power they generate. How can they invest more to organically grow our installed capacity? Further, the looming risk that the country will not honour agreements signed with businesses is a major discouragement to potential investors, such as some elements of the government calling into question the agreement signed with Azura Edo IPP, the only privately-owned world-class IPP built in Nigeria in recent times.

It is not out of place for the curious Nigerian that cares about true growth of the country to wonder why it is believed that signing a “country to country” agreement between Nigeria and Germany is the silver bullet needed to solve our long-suffered power sector issues. Why do we continue to look overseas for solutions to the NESI when the best and possibly only solutions are staring us in the face? Nigeria’s continued search overseas is akin to a family that lives on the banks of a very clean stream but treks several kilometres each day to buy water from a man that collects the same stream water, bottles it and sells to them at a profit.

The solution to Nigeria’s generation problem resides squarely in completing the privatisation of the NESI. What obtains now is a NESI that is partially privatised, but still suffers from regulations and government influence that has stifled organic growth and private investment. The NESI regulators should keep in mind that they cannot regulate something that does not exist. They should, therefore, throw their full weight behind the private companies in the power sector and allow them to grow organically to better serve Nigerians.

Dr Chukwueloka Umeh

Managing Director/CEO of Century Power Generation; Chief Operating Officer of Nestoil Groupchukwuma89@gmail.com

-

‘It Is Difficult Investing in an Unpredictable Power Sector Environment’

- by chukwuma89@gmail.comYears after unbundling the power sector, teething problems still exist, making it impede economic growth. The government recently said it would allow for a cost-reflective tariff, but agitation against the move culminated in the National Assembly putting it on hold. In this interview with FEMI ADEKOYA (The Guardian Nigeria), the Chief Operating Officer of Nestoil Group and Managing Director/Chief Executive Officer of Century Power Generation, Dr Chukwueloka Umeh, believes the intervention of the legislators is not right, especially as underlying issues are yet to be addressed. Excerpts:

Nigeria’s power sector, with all the investments sunk in, remains at the same stage pre-privatisation. There have been issues, especially around the recently postponed tariff increment with some users saying there should be improved power supply before the increment. Where is the sector today, and as a rocket scientist, is the problem a rocket science that cannot be solved?

The problem in Nigeria’s power sector is not rocket science, and if it’s rocket science, you have rocket scientists that are able to deal with it. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t get it right. Well, there are several factors that I think a lot of folks don’t understand about our sector. You know, there’s a lot of conversation in the sector where we will say, yes, we’re willing to pay more money for electricity as long as we are sure we’ll get power 24/7 coming into our homes, our offices, our factories and whatever you have. However, it’s a little bit of a chicken and egg situation; if you don’t pay enough, the power sector doesn’t get fixed. If the power sector gets fixed and you don’t pay enough, it can’t be sustained. So there’s a little bit of dance to do around there. We have a value chain that we speak of and the value chain, if we focus right now only on gas-fired power plants, we’re talking about gas production, gas transportation through pipelines or whatever means you have and the power generation companies (GENCOS), and then you transmit the power through transmission lines and finally get to distribution networks. The distributors now take power and distribute it to their customers’ homes, factories, and offices. This is the entire value chain. So, gas flows from one site, all the way to the GENCOs to generate the power, and then it flows all the way to the customers. Then the money flows from the customers all the way back to pay everyone along the value chain. If any of these pieces is broken, the power sector doesn’t work. And it sounds very simple.

However, the amount of investment needed to make this value chain work is humongous. If you want to produce enough gas to fire a 495-megawatt power plant, you need to invest at least $250 million for a brand-new processing plant. Now, I’m not even talking about the investment that the gas producer makes to drill in his fields to bring out the gas. This is just the processing facility, and then you need to run pipelines, depending on where the plant is situated. If it is situated right next to the gas processing plant, it could cost anywhere from a couple of million dollars to get the gas to the GENCOs or hundreds of millions of dollars to build a long pipeline to get it where it’s going. Currently, the AKK pipeline is about to be built. The AKK pipeline is over 600 kilometres long, and it costs several billion to build a pipeline. Someone is making that investment.

Beyond that, someone is also going to make the investments to upgrade our transmission lines in the country. That’s a whole lot of money. We’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars to build. And then finally, we get to the DISCOs. The DISCOs, when they were sold; what we were told was that the Discos have ATCL losses of around 45 per cent. That is the Aggregated Technical Commercial Collection (ATCL) losses. Now, what we’re finding is that those DISCOs, some of them have ATCL losses above 60 per cent. What that means is, for example, if you give them 10 megawatts of power, and they sell, they are able to collect only 40 per cent money for the power that they’ve given. Everything else is gone and lost. How can the DISCO survive? You can’t run a business this way.

That means it is an issue with the tariff system. Is the MYTO still working as at today, is it still relevant?

Within the tariff structure that we have today, what we’re working with is the Multi-Year Tariff Order (MYTO). The MYTO was set up by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) to encourage investment, and to make sure that customers are not getting price gouges. It’s a nice system in theory, but in practice, it is not working.

It was inside the MYTO that about 38 per cent of the whole tariff goes to GENCOs, about eight per cent goes to the transmission line, and about 48 per cent goes to the DISCOs. And then there’s another six to seven per cent that goes to the VAT, to the government and then services. When you break that down, the question is; how much is actually available for the entire value chain to work? It is quite small.

Today, residents are charged, I think maybe N26 now to N29/kwh. Businesses are charged anywhere from N30 to N46 depending on the Discos. On paper, it sounds good; however, in reality, that’s not enough money for these businesses to run the value chain and make it work. So, we need to go back to the drawing board, and my argument has always been, let’s look at a sector that has worked in Nigeria, which of the privatized sector has actually worked, and the only example I have right now is the telecoms industry.

What did we do differently? The government completely divested from telecoms. What happened after that? MTN came to Nigeria, and they put down infrastructure. I can argue that the tariff that MTN was charging that year was more expensive than the tariff that they were charging anywhere else in Africa. But what happened thereafter? Other businesses started coming to invest in telecoms. So today, you have GLO, you have Airtel, and you have 9mobile, and so on. And because they are competing, the tariff has gone way down, because of competition, there are different telcos. You can constantly see that they are driving to give better services; they are driving to give better tariffs to the end-user. So, the competition has made the price stay competitive so people can actually get a good service at a price that makes sense to them. It’s not the government telling them what to charge.

Are the businesses within the value chain charging what they need to charge to be able to provide good service? Are they charging the tariffs that made sense to be able to make the investment needed to have the infrastructure value? But they also have competitors. And it is the competition that drives pricing. If the same were to happen in the power industry, companies would come to make required investments across the entire value chain to make it work. But this is not the case that is being put forward by the different regulators that the government has set up. The visible outcome today is that they are stifling growth in the country. They are stifling growth across the energy industry.

Can you throw more light on that area? How are the regulators stifling the sector?

It is important we keep talking about it. Some years ago, NERC put out some regulations that were supposed to help renewable energy sources come up. The estimation was that by 2020, this year, we will have about 2000 megawatts running mostly from solar. How many megawatts have we put in solar? If we pull one over and over and we are not seeing the result, isn’t it time for us to start thinking completely differently? You can’t keep doing the same thing and expect a different result. It does not work. It has never worked, and it will never work. It is time for us to take a very different approach. Stop looking at what they did in India or what they did in London or what they did in Argentina. We know what they did. The experts have come to tell us, we have written regulations by experts. A lot has been spent yet no solution in sight.

What can be done to really revamp the sector and make it work?

We spent millions and millions of dollars in this country. That’s why it’s still not the right way to get it done. We have created a power sector recovery programme, PSRP. It’s not working. I argue that it’s time for us to do it differently and deregulate the sector. I’m not telling the government to close down all the regulators, you can keep them there. They have created some nice regulations that we can actually use. Don’t scrap all of them because we can use them. However, we need to understand that it’s a brand-new market that we’re trying to grow. So put the horse before the cart. Allow the sector to grow, and then you can regulate it. In allowing the sector to grow, allow the private companies that are willing to make the investment to make their investments, charge what they need to charge, and then let competition drive the prices down.

Let’s talk about regulations and regulators. How are they preventing the sector from growing, and can you kindly give us an example of how they impede the sector?

I am in generation, and we have the plan that we designed from scratch between 2012 and 2015. We initiated a power purchase agreement with the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc. (NBET), the bulk trader at a certain tariff. Well, guess what? From 2015 till now, nothing has happened. Several of the regulations that we worked under have been changed, several of the agreements that we had initially have been changed. How do we invest money in an uncertain environment? You can’t. The investor will not give you one dollar to invest but the money is there ready to be invested, but nobody is going to give it to you in the uncertain environment that we are in.

You sign an agreement today, in two years it is obsolete, and you can’t even enforce it. So, the rule of law to enforce the agreements is not there. How can you invest? You borrow money on a certain day when a dollar was N360 but today, a dollar is N475. The investment you made has completely gone. The expected returns completely eroded. How can you plan? The MYTO, however, is still at the same level. We were told that on July 1st, we were supposed to see a new tariff. Just before that day, what happened? The National Assembly supposedly got together with the DISCOs and said, oh, we’re not ready for that, let’s move into next year.

The increase that we were supposed to see in tariff has gone away. But Nigerians still expect power to come; it is not going to come. I said this year in, year out, as long as we keep doing this, the way we are doing it now, we would never see any additions, any meaningful action to the power industry. That’s what we see today. So, every year, I can say the same thing, and every year, you’re going to see the same result. A new minister comes in and says by the end of the year we will see 10,000 megawatts added to the grid, it hasn’t happened; and it’s never going to happen unless we change the way we do things.

What policy and market issues are needed to be resolved to facilitate investment for the stability of the power industry?

The policies guiding tariffs and the regulations thereof, and the ability of GenCos to directly sell power to DisCos or end-users need to be relaxed in a way that is investment friendly. They need to be relaxed to allow a free market to exist. For investments to come into the sector and be spent, potential local and foreign investors alike need to see that policies are stable, agreements entered into between companies, and government-related entities are respected once executed, and that our legal framework fully protects such agreements.

Why can’t the GENCOs and DISCOs invest in the power themselves with sufficient metered power for everyone before talking about cost-reflective tariff? I believe this should be available first.

It is a good one; however, I ask you this, have you ever gone to a bank to try to borrow money? If you go to try and borrow money from the bank, the bank wants to see what you are going to use that money for, and how are you going to pay back. Where are you going to pay the money back from? Is it from the money that you make from that business that you’re trying to build?

So, you need to show your business model first of all and be sure that the business can actually pay that money back. Without that, no bank will give you N1. It is the same way for a GENCO to build the plant. For example, a 500-megawatt plant, they need to spend about $700 million, not Naira. They need to see that the money that they are going to make, they can pay it back. If a Disco is going to invest in providing infrastructure, transformers, lines and so on. Guess what, that Disco also needs to show that it can collect enough money to pay back for the investment that they’re going to make. They need to show a viable business. Without showing it, they cannot raise the money they need to invest. This money is not coming from our pockets, it is coming from loans. They need to show that they can make money before they get the power to make investments. In the same way, you don’t ask someone in an airline company to bring planes first before they know that they can charge a high price or whatever price they need to be able to pay for the plane and pay the salaries of all workers. It doesn’t happen that way. This is business.What role is the current gas pricing regime playing in the current bottlenecks being encountered by the GENCOs?

Gas pricing is one of the most important determinants of generation tariff, that is, electricity tariff is most sensitive to gas price. In order to produce and transport sufficient gas to GenCos, gas producers need to build, operate and maintain their gas production and processing infrastructure, which requires massive investment. Gas transportation via gas pipelines or virtual pipelines (trucks or barges) also requires sizeable investments to set up. These investments would, therefore, need to be amortized over time in the form of cost-reflective gas supply and gas transport charges, which are ultimately passed through to electricity tariff. Without proper gas pricing, there will be no investment in gas production and transport infrastructure. If this situation does not change the power sector cannot grow, no matter the lip service. Note that presently, only about 21% of the gas produced annually in Nigeria is used locally for power generation, petrochemicals, and others.

chukwuma89@gmail.com